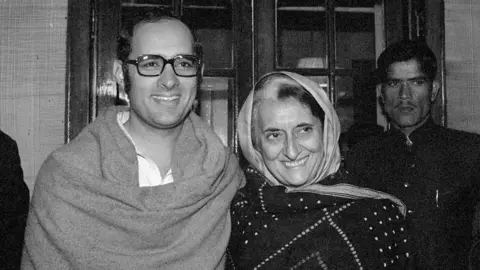

United Archives via Getty Images

United Archives via Getty ImagesAt midnight, June 25, 1975, India – young democracy and the world’s largest – frozen.

Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had just declared an emergency installation. Construction freedoms were suspended, opposition leaders are closed, pressed, and the constitution turned into a tool of absolute executive. In the next 21 months, India was technically still democracy, but functioned as anything, but.

Trigger? The Judgment of the Bomb by the Gandhabad High Court found Gandhi Crieti for election abuses and annulled the election win from 1971. years. Dealing with the political disqualification and growing wave of street protests by Jaiaprakaš Naraian, Gandhi decided to declare the “internal emergency” in accordance with Article 352. years, referring to threats based on stability.

As historians, Srinath Raghavan recorded in his new book on Indir Gandhi, the Constitution enabled broad powers during the urgency. But what followed was “extraordinary and unprecedented strengthening of executive … invalid court surveillance”.

Over 110,000 people were arrested, including large opposition political figures, such as Morary Dessai, Jioti Basu and LK Advani. Prohibitions are hit by groups from right-handed to the ultimate left. Close were crowded and torture was a routine.

Courts, personalized by independence, offered small resistance. In Uttar Pradesh, which is in prison in prison the most detainee, and no order for detention is excluded. “No citizen moved the courts to implement their basic rights,” Raghavan writes.

During the controversial family planning campaign, it was estimated that 11 million Indians were sterilized – much coercion. Although officially state, the program is widely believed to be orchestrated Sanjai Gandhi, an unclear son of Indira Gandhi. Many believe in the shady other government, led by Sanjai, had an uncomprediable power behind the scenes.

The poor were the hardest affected. Cash incentives for surgery often amounted to monthly income or more. In one Delhi Neighborhood near Uttar Pradesh – he called “the Castration Colony” (places in which coercive sterilization programs took place) – women said that they were made Bevas (widows) by the state as “our people are no longer men”. Police in Uttar Pradesh I recorded over 240 violent incidents related to the program.

In their book on Delhi under emergencies, civil entity activists John Daial and the press release of Bose wrote that officials were under intense pressure to meet sterilization quotas. Junior officers applied the order ruthlessly – said the contract workers were told, “there is no advance, unless you get vasectomy.”

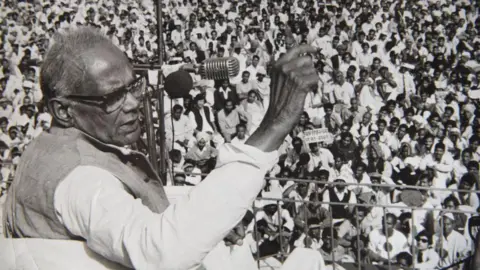

Getti images

Getti imagesIn parallel, the mass-urban “cleaning” was demolished almost 120,000 slums, which was part of only 700,000 people in Delhi, as part of a gentle campaign described by critics as social cleaning. These people were thrown into new “relocation colonies” away from their jobs.

One of the worst episodes of slum’s demolition occurred in Delha’s Turkman Gate, the neighborhood of the Muslim majority, where the police dropped protesters by resolving demolition, killing at least six and moving thousands.

The press was silent overnight. Ahead of ambulance, the power of newspapers in Delhi was interrupted. Until morning, censorship was the law.

When the Indian Express newspaper finally published his 28th edition – delayed by turning off the power – left an empty space where it was needed to be editorial. The citizen followed the suit, printing empty columns on the signaling censorship. Even National Herald, he founded the first Prime Minister of India and the father of Indira Gandhi Javaharlal Nehru, quietly lowered his Masthead slogan: “Freedom is in danger, he defends him with all the powers.” Shankarovo a week, a satirical magazine known for cartoon, is fully excluded.

In its book – personal history of emergency – journalist Coomi Kapoor reveals the scope of media censorship through detailed examples of obscuration orders.

They included prohibitions on reporting or photography of slum demolitions in Delhi, conditions in the maximum-security prison of Tihar and development in countries that rule oppositions such as Tamil Nadu. Family planning coverage is suitably controlled – “unwanted comments or editors” is not allowed. Even stories that are considered trivial or embarrassing: not “sensational” reporting on the infamous Bandit and we do not mention the Bobbish actress caught in London.

Kapoor also notes that BBC Mark Tully, together with journalists from Times, Newsweek and Day Telegraph, was given 24 hours to leave India to sign “Censorship contract”. (Years after the Gandhi returned to power, Tully met with the boss of BBC. He asked how he felt he lost public support. She smiled and said the rumors on the BBC. “)

Some judges pushed back. Bombay and Gujarat High terrains warned that censorship could not be used for “brain washing”. But that resistance was quickly drowned.

Keystone / Getty Images

Keystone / Getty ImagesThat wasn’t everything. In July 1976, Sanjay Gandhi Pushed The Youth Congress – The Governing Congress Party’s Youth Wing – To Adopt His Personal Five-Point Program, including Plantation, Refusal of Dowry, Promotion of Adult Literacy and Abolytion of Caste.

The Congress President of DK Barooah sent all state and local committees to implement five points of Sanjeva, together with an official 20-point government, efficiently merge state policy with Sanjai’s personal crusades of Sanjai.

Anthropologist Emma Tarlo, the author richly detailed ethnographic work in the period, wrote that in emergency situations were undergoing “forced elections”. It was also a temporary point for industrial relations.

“The latest remains of workers’ class policies were insufficiently deleted,” Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratatin Anil in her book in their book calls “Indian first dictatorship”. About 2,000 unions leaders and members were closed, the attackers were forbidden and the benefits were used by workers.

The number of people lost lost to stop – from 33.6 million in 1974. at only 2.8 million in 1976. years. Strikers fell 2.7 million half a million in half a million. The government has also weakened its private sector grip, helping the economy that after years of stagnation is adhered to. The Industrialist JRD Dad praised the “refreshing pragmatic and result-oriented result”.

Despite the hard degree, emergencies saw them as a period of order and efficiency. Neder Malhotra, a journalist, wrote that in “Fights in the early months in the emergency situations in India some kind of calm that it was not known for years”.

The trains ran on time, strikes disappeared, a production rose, crime fell, and prices have fallen after the good 1975. Monsoon – bringing much needed stability. “One Fact is Conclusive Proof of the Quiescence of the Middle Class – That Hardly Any Officials Resigned in Protest Against The Emergency,” Writes Historian Ramachandra Guha in His Book India After Gandhi.

Sondeep Shankar / Getty Images

Sondeep Shankar / Getty ImagesScholari believe that ambulance measures are largely limited to northern India, because the southern states were stronger regional parties and yet the sweetness of civil societies that are limited central transmission. Gandhi’s Congress Party, which ruled the federally, had weaker control in the south, giving regional leaders to more autonomy to resist or moderate draconian policies.

It was formally formally completed in March 1977. years after Gandhi called the election – and lost. The new JANATA GOVERNMENT – the coalition of the ticket from the cloth tag – overturned many laws that passed. But deeper damage was done. As many historians wrote, the ambulance revealed how easily democratic structures can be exhausted from within – even legally.

“No wonder they feel urgently in India … The Indiration Suspension of Constitutional Rights appears as a sudden caretaker of the liberal-democratic spirit that animated Nehru and other nationalistic leaders who were 1950. written by the historian Gian Prakash.

Today, an emergency is worth the emergency in India as a brief authoritarian interlude – aberration. But that framing, warns Prakash, gives birth “self-confidence in the present”.

“It tells us that the past is really the past, it’s almost a history. Indian democracy, and without lasting damage, and without problems, and no permanent damage and without durable, without deficiencies.

“It is basically a depleted concept of democracy, one that considers only certain forms and procedures.”

In other words, this perception ignores how much fragile democracy can be when institutions do not include the power to find.

The ambulance was also a warning of the danger of the hero – something embodied at the high political person Indira Gandhi.

Return 1949. year, Br Ambedkar, the architect of the Constitution, warned the Indians against the teaching of his freedom “Great Leaders”.

Bhakti (commitment), he said, was acceptable in religion – but in politics he was a “safe path to degradation and possibly dictatorship”.